Review: Ali Smith, How to be both (2014)

by mysaladdayswhen

How we interact with art says as much about us as it does about an artwork. It was passing through the Van Gogh Museum where I first discovered the impression an artwork can leave on you inner being. Staring intently at a picture of blue irises against a yellow background, I was struck by the emotional stamp Van Gogh left on this painting. Not just a still life of some flowers, this work captures a feeling of pure delight, a sense of wonder at the beauty that can be found in something so simple. Just looking at this painting made my spirit soar, and suddenly I felt as though I understood not only myself, but Van Gogh’s choice to render this image, as well as the lure of the world.

Ali Smith’s multifaceted Man Booker shortlisted novel How to be both (2014) explores, amongst many other things, how we see ourselves in relation to art. It is simultaneously a story of the quattrocento Renaissance artist Francesco del Cossa and also that of George, a sixteen-year-old girl who has suffered the loss of her mother. The story is divided up into two parts, and the part you get first is dependent on your luck at the bookshop. In my copy, I met Francesco before George. What I find most interesting about How to be both is how Smith plays with mirrors, gender (one of the great unsaids of the novel), and questions of seeing all to the effect of creating an argument for empathy. So much of what the novel revolves around is the importance of seeing the world through the eyes of another; ultimately, this becomes an argument for the importance of art itself.

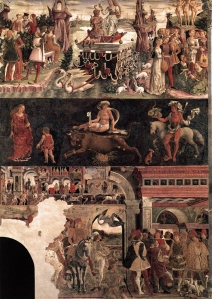

It would make sense that a novel about art thematises acts of looking. As an artist, Francesco’s world is dominated by the visual. She is excited by colour, form, and creating beauty. Eyes recur throughout her artworks, and assert the power of the artist to make their audience connect with the painting. Most of Francesco’s section of the novel revolves around the creation of her magnum opus, the allegorical frescoes of March, April and May in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara. In one section of the picture, Francesco paints a horse who has ‘eyes that can follow you around the room’ (the most famous example of this effect is the Mona Lisa). A lot of the novel explores the point at which we stop seeing and we start being seen. The artwork, even if it isn’t alive, stares right back, and holds us:

those are the God eyes and whoever has them in a painting or fresco holds the eyes of whoever looks at the work, and this is no blasphemy, merely a reasserting of the power of the gaze back at us from outside us always on us.

The artwork becomes inescapable; for a moment the viewer is caught by the artist and pulled into their imagined world.

Fast forward to the twenty-first century, George’s mother is holding forth about questions of looking, ‘And which comes first? her unbearable mother is saying. What we see or how we see?’. In this part of the novel, the gaze of the artist turns into the gaze of modern surveillance cameras. Smith explores the difference between being looked upon as an object of sexual desire and as a person being monitored. When George’s internet anarchist mother takes her children to Italy on a whim to see Cossa’s frescoes, she explains that she thinks her erstwhile friend (who she possibly loved) may have been spying on her for the government. George cannot understand why her mother finds the gaze of her friend erotic, to which her mother replies, ‘Seeing and being seen, Georgie, is very rarely simple’. All through the novel there is an awareness of surveillance, and the complexity of George’s mother’s relationship to being watched mirrors Francesco’s desire to have her work gaze back onto the viewer. The eyes are everywhere, and those who are able to direct vision in How to be both are those who hold power.

Besides representing control and authority, looking and vision are also part of Smith’s exploration of empathy. This theme is part of How to be both’s framework of deliberate artifice; the sincere rendering of empathy is an element of Smith’s play with the novel’s form. For homework, George and her friend Helena have to write a presentation about the difference between empathy and sympathy. In a moment of insight, George imagines doing the presentation about Francesco, making up his/her whole world and life story, seeing as very little is known about the artist in reality. Francesco’s section of the novel, it seems, it just a momentary figment of George’s imagination:

You’d need your own dead person to come back from the dead. You’d be waiting and waiting for that person to come back. But instead of the person you needed you’d get some dead renaissance painter going on and on about himself and his work and it’d be someone you knew nothing about and that’d be meant to teach you empathy, would it?

Smith’s metafictional description of her story of Francesco made me do a double take: was the whole first part of the novel just a flash in the mind of a teenage girl?

Having read George’s section after Francesco’s, I wondered how my reading of How to be both would change if I happened to have a copy that went the other way around? Would I see Francesco only as a figment of George’s imagination? Is this just part of Smith’s deliberate play with form and artifice through the novel? An intellectual game of puns and mirrors? I doubt this. If one of the major themes of the novel is to express the need for empathy, Francesco’s story is probably meant to make the reader see through the blind eyes of history. The reader is given a vision into an artist who could have been lost to time; the only reason we know of Cossa’s existence is because a letter of his was found in the late 1800s, asking the duke of Ferrara for a larger payment for his frescoes. The motif of vision is constant in Francesco’s section, and she is particularly empathetic to those who can’t see. Smith describes Francesco’s rendering of the blinded Saint Lucy, to whom she gives eyes as though they were flowers, because she thinks it would be cruel to deprive Lucy of her vision. Francesco quotes the Renaissance art theorist Alberti, ‘the eye is like a bud’; it is through our eyes that we perceive the world, and from which things grow in our lives. The act of seeing in this novel is tantamount to empathetic feeling. To really see, to perceive, is to love. And by writing a novel seeking to identify with two (seemingly disparate) characters, Smith may be asserting that the creation of art itself is an act of empathy and love. How to be both reinforces that great art makes us emotionally react and see the world through a different pair of eyes; that it has the capacity to make us see beyond ourselves. As George’s mother says, ‘Art makes nothing happen in a way that makes something happen.’

In How to be both, Smith presents the limitlessness of art and the empathetic effect it can have upon individuals. Even the title draws upon the idea that empathy means being both ourselves and someone else for a moment. And what is fiction but inhabiting the mind of another? This novel is a testament to the power of the artist/writer’s capacity to create a world and have the viewer/reader inhabit it. I must admit, after reading How to be both, I spent hours trawling through articles on Smith, Cossa, and Ferrara. I’m now determined to see these frescoes myself, and hopefully catch the eye of that god-like horse.